Murder en Plein Air

Background to Murder en Plein Air

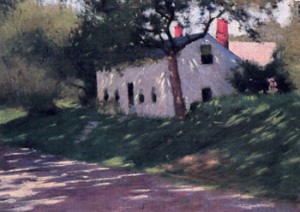

The next time you’re at the Arts Complex Museum in Duxbury, Massachusetts., be certain to seek out a small, 1889 canvas, shown at right, titled The Roadside Cottage, done by Dennis Miller Bunker . Along with several other works in the room, it was painted in the town I’ve called home, off and on, for the past four decades. For several years in the late 19th century, Medfield was a thriving artists’ colony. Remarkably, the cottage shown in the painting is still standing.

It started me thinking… what if such a painting held clues to an unsolved murder, or perhaps even a murder that had never been reported? And what if, in the process of trying to track down those clues in that painting, there was the discovery of an equally interesting mystery going on in the present? It sounded to me like something that ought to occupy Liz Phillips, Detective John Flynn, and the various characters who populated A Murder in the Garden Club and Murder for a Worthy Cause.

It could also be an opportunity to tell two stories simultaneously. The first would be about the events that led to the 1889 murder: the protagonists, the murder’s investigation or lack thereof, and its aftermath; and how those long-ago clues would be uncovered in the present. There might even be people who still cared deeply about such an event though it happened more than a century ago and would try to thwart an investigation. The second would be a contemporary story with distinct parallels to the one more than a century earlier. Its solution would take unpredictable twists through a modern-day landscape.

I completed the manuscript in 2009 but work to polish it was devoted instead to write The Accidental Spy. The publication of “Murder en Plein Air” would mark the fifth installment in what I now call the ‘Horticultural Quarter’. I had time recently to revisit Plein Air and, with some work, it can be a worthy addition to my title list. All I need is… time. Until I get that elusive block of time, feel free to sit back and enjoy the first chapter of the story!

Synopsis

When Hardington antiques dealer Roland Evans-Jones offers to lend a painting to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts for an upcoming exhibition, he believes he’s increasing the value of a canvas by a minor American Impressionist painter by a few thousand dollars.

But when the painting is brought to the museum for cleaning, four pages from the artist’s diary are found wedged in the frame; pages that document a murder at the town’s summer artists’ colony in 1889. What’s more, the culprit named is Edward Merrill Cosgrove, one of America’s most prominent painters at the turn of the 20th Century.

Liz Philips and Roland enlist the services of Detective John Flynn to help find out whether there is a record of the events described in the journal. He agrees to help his friends. But when the purported burial site is excavated, there’s suddenly a very new mystery on Flynn’s hands: a gold bar is found, and it has been in the ground for only a few years.

What follows are two intertwined stories: the first is of a never-reported murder and its aftermath. The 1889 murder has the potential to destroy one artist’s reputation while causing a reappraisal of another’s. Even after the passage of more than 120 years, people still have much to gain and lose from the corroboration or debunking of the newly discovered journals.

The second story is of greed and cunning in the internet age, and of the violence that lurks behind those get-something-for-nothing spam messages that populate computer inboxes.

Murder en Plein Air, the third installment of the ‘Hardington’ series, weaves these two stories together. It also puts Liz Philips and Detective John Flynn back into close proximity, where their mutual attraction becomes increasing evident.

MURDER EN PLEIN AIR

1.

Tuesday

“I loathe driving inBoston,” said Roland Evans-Jones. “It’s a complete and utter disaster. The roads are in a perpetual state of disrepair. The traffic is a nightmare. My God, that SUV is coming straight at us! Brace yourself!”

Liz Phillips said nothing. She glanced at the oncoming Jeep, which was safely on the other side of the Arborway.

“In what third-world country did these people learn to drive?” Roland said, his exasperation rising. “And doesn’t anyone stop for a red light?”

“Roland, you’re not driving,” Liz said patiently as she eased her Jaguar forward when the light turned green. “Yet you’ve been complaining non-stop for twenty minutes. Besides, you once told me you drove all over Italyfor a year and they were the worst drivers. How did you survive that?”

“I was much younger,” Roland said, then hurriedly added, “And I wasn’t holding something precious in my hands.”

Liz smiled to herself. “Yes, I’m sure it was easier back then. Well, we’ll be there in seven minutes. You could also check your painting. I don’t think you’ve inspected the wrapping in the last two blocks.”

Liz Phillips, president of the Hardington Garden Club and Roland Evans-Jones, Liz’s friend and lone male member of the garden club, were enroute to theMuseumofFine Arts. Liz was 57, blonde and trim. Roland, who had given his age as 72 for at least five years, had a full head of white hair and carried the extra weight of a man who had enjoyed life to the fullest. When Liz has first offered to accompany him to the museum, he had insisted that he could take the commuter train intoBostonand take a cab to the museum. Liz knew he would have stood, paralyzed, in front of Back Bay Station, seeing a master art thief behind the wheel of every taxi.

Roland checked the bubble wrap on the painting in his lap. It was still securely around the frame, increasing the bulk of the picture by half.

Liz made the turn from the Arborway ontoHuntington Avenueand the greenery of Olmstead’s Emerald Necklace was replaced by the gritty Mission Hill neighborhood. Roland responded by locking the Jaguar’s door.

“Five minutes, Roland,” Liz said. “Then your painting will be safe.”

* * * * *

The Painting Conservation Lab of Boston’sMuseumofFine Artsoccupied a surprisingly spacious suite of rooms in the building’s basement.

“Let’s have a look at it,” said Polly Morse. She smiled and held out her hands. Morse was one of the museum’s curators of special exhibitions. She looked to be in her early sixties, was dressed in a well-tailored suit, and she stood a full head taller than Roland, with silver hair worn in an Egyptian bob and black lacquer glasses. Roland reluctantly handed over the package.

Morse tenderly pried off the outer tape Roland had applied, then unwound multiple yards of plastic bubble wrap.

“You may want to know that we used less padding than this when we sent off The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit to New York,” Morse said cheerfully as she peeled off the last of the bubble wrap. At last, the painting could be seen.

“Beautiful,” she said, holding the painting at arm’s length. “Magnificent.”

The painting, twelve inches by sixteen inches, was of a small, rectangular house on a country road.

“The Wayside Cottage,” she said, with a hint of reverence in her voice. The painting was signed and dated: Alan Churchill Lawrence 1889.

“I can’t tell you how excited we are to get this painting, Mr. Evans-Jones. I sometimes think museums swap the same hundred and fifty American Impressionist works back and forth, and just dream up new titles for the catalog. This is refreshing. It’s new to viewers, it’s in wonderful condition, and it’s spot-on for the exhibition.”

The exhibition in question was ‘En Plein Air: Nineteenth Century New England Art Colonies’. The exhibition was planned to open in January, three months hence.

“Lawrence’s body of pre-1900 work isn’t large, and the only works of his in MFA’s collection are two of his Falmouthseries and an early commissioned portrait,” Morse said to no one in particular, continuing to examine the painting. “What makes this exciting is that we’ll have the loan of Dennis Miller Bunker’s painting of the same structure and John Leslie Breck’s ‘The Pool, Hardington’, all from the same summer and all executed within a few weeks of one another, with the artists all living in the colony. We’ll group them together, of course.” She looked up from the painting at Roland and smiled.

“Of course,” Roland said, seemingly still coming to grips with the idea that his painting was going to be at the mercy of strangers.

“I understand the painting has been in your family for a long time?”

Roland nodded. “The provenance is solid. I acquired it with an estate of a local family – Hardington, I mean. A couple, both in their nineties, died within a few months of one another and the children – who were in their sixties and seventies – didn’t know what to do with the home’s contents. I bought it all. Everything. Furnishings, furniture, clothing, art.”

“When was that?”

“Nineteen sixty four,” Roland said with certainty. “It was my first estate purchase. When I think of what I let some of that furniture go for… But the painting has hung in my own home ever since.”

“We’ll do the conservation work, of course, as agreed,” Morse said. “I’ll introduce you to the restorer.”

At a table on the other side of the room, a woman in her mid twenties, thin and dressed in a red Harvard sweatshirt, looked up in anticipation and moved aside a small painting immediately recognizable as a Childe Hassam painted at Old Lyme.

“Lori, this is Roland Evans-Jones. Mr. Evans Jones, this is Lori Browning.” Morse held out the painting to Browning. “And this is going to be the focus of your attention for the next few weeks. Alan Churchill Lawrence’s The Wayside Cottage.” Morse turned to Roland and Liz. “Lori may look young, but she is in her fifth year with us and she has handled everything from Sargent to Renoir. She has a superb eye and a delicate touch. Your painting couldn’t be in better hands.”

Browning gave a quick smile, then pulled a lamp closer to her and held the painting at various angles. “It’s never been cleaned?” she asked Roland.

“Not to my knowledge,” he said.

She nodded. “Actually, that’s good.” She took out a magnifying glass from her desk and examined a corner of the painting. “Some of the things we used to do to paintings to restore them actually made things worse.” Browning tilted the painting to near-horizontal and again examined an area. “The varnish is slightly discolored. I’ll take that off and apply something that will keep the paint underneath in good shape for another hundred years. Do you mind if I remove the frame?” Browning asked. “I mean, I’ll have to remove it to clean it. Do you mind if I remove it now, in front of you?”

Roland looked nervous. “By all means.”

Browning examined the back of the painting and, with an X-acto knife, sliced through a layer of ancient brown paper. In four quick but delicate strokes, the paper was off and she placed it to the side of her work table. She was picking up a pair of pliers when Polly Morse picked up the painting, now resting face down.

“What’s this?” she asked.

Wedged into the frame were several folded pages of white paper, dense with handwriting.

“Give me a pair of gloves,” Morse said to Browning, who pulled a pair of white curatorial gloves from the drawer of her desk.

Morse donned the gloves and pulled gently at the paper. “It’s wedged into the frame,” she said after failing to free the paper. “Let’s get the frame off.”

Browning used pliers and a tack hammer to separate the painting from its gilded frame, and the papers were free. They lay, folded, on Browning’s work table.

“It appears we have a message from the past,” Morse said. “Would you like to read it now?”

Roland nodded his head. “I had no idea anything else was in there.” Then, not wanting to admit he had left his reading glasses at home, he said, “I think as a curator you’re the better person to handle them”

Morse scanned down the page, turned in over, then quickly looked at the second sheet. She exhaled. “My lord,” she said softly. “These are pages fromLawrence’s journal.” And then she began to read.

* * * * *

June 12, 1889

After a hearty breakfast, we set out for a day at the Charles. Breck is keen on us each capturing the pools and eddies by the rail road bridge. I completed an oil sketch and am pleased with the composition, which Bunker also likes and intends to capture from a point about 100 feet north. The talk, as always, is of who will join us next. Frank Benson says he cannot leave his bride and the joke amongst us is that it is the longest honeymoon on record. Will Metcalf says he will join us for two weeks but is vague about which weeks it must be. And as usual, everyone is certain that ‘Cosgrove’s arrival is imminent.’ It has become a morning ritual: ‘Is Cosgrove’s arrival still imminent?’ Mrs. Jeffries is quite beside herself awaiting the purported arrival of this elusive luminary.

Parker chose not to go with us this morning. He instead says he wishes to sketch the factory girls and has walked into town. There is a group who sorts the straw out of doors and he is keen to capture their movement. Bunker says Parker is keen to capture a different movement on the part of these girls and that the boardinghouse will soon have a straw path from Parker’s room to the porch landing.

A note in the afternoon post: Edwards says three paintings have been placed for approval with ‘the Whitney family’ who are furnishing their newly built home in the Back Bay. Maddeningly, he does not say which three paintings. I have queried him by the evening post.

June 13, 1889

Mrs. Jeffries has laden us down with meats, cheeses and loaves of hearty bread and must believe we are bound for California rather than a riverbank less than a mile distant. Bunker says he will need new britches before the summer is done, such is the increase in his girth. There were six of us this morning: Bunker, Breck, Harkness, Thomas, Grimes, and myself. Parker is again sketching his girls at the straw handbag factory, which draws much snickering.

I have improved upon my sketch of the Charles, lowering the horizon to great effect, the better to capture the magnificent summer clouds in the style of Sisley. If the weather holds, I shall begin full work tomorrow. This evening, I have devoted to completing the oil of the little private cottage adjacent to the boardinghouse. I am quite pleased. Bunker admires the painting greatly and implies he will take up the same subject when he has completed his oil of the Charles.

Edwards apologizes and reports that the Whitneys are a prosperous family and that the three paintings are from the seaside series of last August. I have given him pricing instructions.

June 14, 1889

Rain. I have spent the day fixing imperfections in the painting of the wayside cottage and in conversation with Bunker and his friend Chas. Loeffler, of whom we have seen little as he spends his days composing music in his room. This evening, Loeffler entertained us with his violin. Mrs. Jeffries has plied us with tea and scones until we shall burst. Nothing from Edwards.

June 15, 1889

A chorus of heavenly hosannas has come, for we await the arrival of Edward Merrill Cosgrove, who has wired Breck that he is to arrive on the 16th and will stay with us one week, more if he is as impressed with Hardington as Breck has extolled it to be. Bunker is to move out of the little cottage so that Cosgrove may have a fitting domicile for an artist of his stature and a modicum of privacy for his work.

Our little artists’ colony has finally found its voice. Cosgrove is in a position of influence and has single-handedly made the reputation of Kennebunkport as John Brown did Appledore Island. Breck says only half in jest that Mrs. Jeffries will become our Celia Thaxter.

Edwards reports the Whitneys returned two paintings but have kept the one of Lydia and Josephine at the Falmouth beach with the fog effect for a while longer. The Whitneys, according to Edwards, believe it an outstanding example of modernism. He also says a Mrs. Haskell and daughter have come in twice to view ‘seaside paintings’. And for this I pay him a commission!

June 16, 1889

Edward Merrill Cosgrove arrived in full regalia late this morning. He was met at the Hardington station by pre-arranged coach and brought to the boardinghouse where he pronounced us all a fine lot. We all stood in line at attention, awaiting his inspection, and I felt I was back in school.

He is a bear of a man fitted out for sport rather than for painting. His full beard is brown without a fleck of gray and his hair is full and in the European style. He laughs with a great chortle at jokes both made by others and his own. He is, in short quite full of himself and has changed the character of the colony. Mrs. Jeffries attends to his special diet needs to the detriment of her other lodgers. He has commanded the little cottage. Breck reminds us Cosgrove is a force for good and his opinion is of great value. We shall see.

Our day on the Charles was foreshortened by Cosgrove’s commandeering of all resources, including Mrs. Jeffries’ wagon. I am greatly pleased with my preliminary sketches.

June 17, 1889

The Whitneys have agreed to purchase Lydia and Josephine for $125! Edwards went to their town house to complete terms and reported it is hung in illustrious company in their morning room between a Holland landscape by William Merritt Chase and a Cosgrove Kennebunkport boating scene. Hallelujah for the lovers of modernism!

Cosgrove joined us by the Charles, making very merry of the trip. He did not set up his own easel but, rather, critiqued our own canvasses on his whim. He offers praise to some, faint praise to others. Bunker, he lauds highly and offers advice on texture. He is kind to Harkness though it is clear that he cares little for Harkness’ style. Grimes and Thomas receive encouragement but his praise sounds hollow. Breck is his favorite; he studies the painting currently on his easel as though memorizing it. Parker, who has forsaken his factory girls for the week, is sketching in charcoal and Cosgrove makes only grunting sounds. My own painting he damns with phrases such as ‘patchy effect’ and ‘interesting streaks of gray’.

I would retort that one of my painting now hangs alongside his at the Whitneys, but at dinner last evening he boasted that his patrons adore his work so much that he, Cosgrove, can command them to hang an oil upon a certain wall and he can banish lesser works from the same room or even building. Thus I have kept my tongue.

June 18, 1889

A most peculiar series of events is unfolding. This evening Cosgrove said he would take his supper in the cottage owing to his desire to work upon sketches of the Charles. Yet, upon returning from taking Cosgrove his supper, Mrs. Jeffries reported that no paintings or sketchbooks were in evidence, only that Cosgrove was in his room reading.

Then, toward twilight, two respectable, but not fashionably dressed men appeared at the front door of the boardinghouse. They offered no calling cards, giving only the names Brighton and Carville, but said they must speak with Cosgrove. Mrs. Jeffries repaired to the cottage by the back way to apprise Cosgrove of their presence, making certain that the two men did not know Cosgrove resided in the little cottage and not in the main house.

She returned to tell the two men that Cosgrove was not in residence and she could not ascertain when he would return. The two men became agitated and insisted they would return tomorrow morning and that Cosgrove must appear. When they had left, Mrs. Jeffries informed us that Cosgrove was not in his room. My own room faces toward the little cottage and I have kept watch on the building until near to midnight.

Our journey to the Charles was a productive one. Cosgrove did not review our work and my painting of the river plain with its mountain of clouds is firmly fixed in my mind and beginning to take shape on the canvas. Thomas and Grimes, however, have had their hearts broken by Cosgrove’s words and they talk of cutting short their stays. Breck and Bunker, conversely, are plainly elated by the praise given them by the great man.

Edwards reported by the morning post that the Haskells, mother and daughter, have brought Mr. Haskell, a banker by profession, to see my works. Mr. Haskell immediately demanded to know the sums involved. I have written Edwards that he is not to negotiate with the banker. The price is the price.

June 19, 1889

Here, as best as I can relate it, is what transpired today. Cosgrove joined us for breakfast and learned of Brighton and Carville’s visit. Cosgrove became most agitated that Mrs. Jeffries had even acknowledged that he was in residence and cross-examined Mrs. Jeffries to determine with certainty that the men had not crossed the threshold of the cottage. Only when he was satisfied that they had not did he allow Mrs. Jeffries to attend to her duties, but his foul temper remained.

Cosgrove then left for the telegraph office, demanding that Mrs. Jeffries’ man, Otis, abandon his other responsibilities. When we asked Cosgrove if he would join us at the river, he fumed and said he would come and go as he pleased. We walked to the river, Otis being unavailable. Parker said he would return to the straw handbag factory.

We passed a good day, each of us making progress on our work. Bunker has indeed found an excellent vantage point upriver from my own and I greatly admire the painting that is taking shape upon his easel. Otis came for us about 4 p.m. and said Cosgrove had spent much time in the telegraph office and then taken the train into Boston. The two men, Brighton and Carville, did re-appear about half past nine and Mrs. Jeffries said Mr. Cosgrove could be found in Hardington village. The men were very angry. Mrs. Jeffries was quite upset by the incident.

We passed the evening quietly, though each had his private theory of the two men and some shared theirs. The most popular is that they are detectives come out from Boston to investigate Cosgrove for some bit of malfeasance, though policemen would have shown badges. Another is that they are bill collectors come to seize Cosgrove’s belongings for non-payment, though Cosgrove is known to be a wealthy man.

When the others had retired to their rooms, Parker pulled me aside and said he had spied Cosgrove in the village as Parker returned from the straw handbag factory. He said he saw Cosgrove speaking with a man of some fierceness, ‘a rogue’ as he put it. The men were speaking as conspirators would. He dared not say anything in front of Mrs. Jeffries or the others lest they repeat his story and Cosgrove would know that Parker had seen the face of the rogue.

Cosgrove returned in the evening, saying he had been called to Boston to consult on a portrait. He went to the cottage, said he wanted no supper and demanded that he not be disturbed.

June 20, 1889

I was awakened in the night by a noise of metal against stone. I went to my window, which overlooks the little cottage. There, I did see a lantern burning at some distance from the cottage and, in the light of the lantern, the outline of two men. They worked with picks and shovels upon a small plot of ground for the better part of an hour. Then, in the darkness, they deposited two large filled burlap bags into the hole they had made. Each sack required both men to wrestle it into the hole. They re-filled the hole they had made and smoothed the ground. The lamp was extinguished and I heard no further noise.

In the morning, we assembled for breakfast and Cosgrove was in a jolly mood. He insists we go to the Charles today to paint. I have pleaded a toothache and said I will stay behind.

When they had gone, I walked to the spot where I saw the lantern and there is indeed a largish patch of disturbed earth. I tremble as I write this because I believe that Cosgrove and the rogue friend seen with him by Parker did kill and bury Brighton and Carville behind the cottage.

I dare not report what I have seen because a man capable of the acts I witnessed would not hesitate to inter a third body. Thus, I have settled upon a course of action. In the last few hours, I have inserted into my canvas of the cottage a red peony bush where there is no such shrub. The location of the peony aligns as closely as I can make it to the location of what I believe are the two graves.

The last few pages of my journal from June 12 forward describe Cosgrove’s arrival at the colony. I am sending these pages, together with my painting, to Howard Edwards on the afternoon train with a note that he read these lines and act accordingly, taking care to ensure that my name is not part of the body of information given to the police.

Howard, you are my friend as well as my agent, and I entrust that you will act in a way that will protect me.

Alan Churchill Lawrence

Hardington, Massachusetts

June 20, 1889

* * * * *

The room was silent when the curator put down the papers. Her hands were shaking as she did so.

“Some of the names are a little over my head,” Liz said. “Edward Merrill Cosgrove is the same Cosgrove…”

“Yes,” Morse said. “One of ‘The Ten’, although that was a few years in the future. The physical description of him is perfect, although I don’t remember ever reading that Cosgrove was in Hardington that summer. He did a series of garden scenes and seascapes inKennebunkportthat summer and sailed forFrancein August fromNew York.”

“How do you know so much about an artist’s whereabouts?” Liz asked.

“For an important artist like Cosgrove, their entire painting career is documented,” Browning answered. “Scholars look at the change in styles for clues to influence. When Cosgrove went toFrance, he painted for a period of time with Monet and it changed his color palette for years thereafter.”

“So who areBrightonand Carville?” Roland asked.

Morse shook her head. “That will take some research. We may never know. If I can take a copy of this, I’d like to send it of to some scholars inNew York. I think we could move some things around in the exhibition to display facsimiles of these pages – with your permission, of course.”

“It’s too bad the cottage doesn’t still exist,” Browning said. “Think what that would do for attendance.”

Roland looked at her with surprise. “You’re wrong on that one, Miss Browning,” he said. “The cottage is definitely still there.”

2.

Detective John Flynn traced his finger over the map. Four colored lines meandered and crossed. A series of ‘X’ marks and times lent authenticity and scientific methodology to his creation.

He mused to himself that, eighteen months earlier, he had created similar lines on a map, though that map was ofBoston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood. The lines on that earlier map had indicated the routes over several days, painstakingly recreated, of a burglar with a taste for rape. Flynn and his partner had used his creation to stake out and catch the perp, a 21-year-old Dominican who was now serving a life sentence at Cedar Junction.

But this was a map of Hardington and the four lines indicated known incidents of the local crime of choice, one almost certainly perpetrated by a carload of bored teenage boys. Each ‘X’ indicated a report of a smashed mailbox at a particular time on a particular day during the prior week. By plotting the route of the car on four days, he now believed he knew where the boys lived. More important, he knew where they would go next, and when.

This is not police work, he thought to himself. This is a job for a truant officer.

Not that he had lacked for useful work in the five months since he had joined the Hardington Police Department as its sole detective. A month after his arrival, he had solved the murder of Sally Kahn, the first in Hardington in fifteen years and a killing that would end in two more deaths. Two months ago, he had found the killer of Fred Terhune, a town selectman found dead just as the Ultimate House Makeover television program was about to start work on a home for a needy family.

No, that’s not right, he thought. I didn’t solve those murders. We solved those murders. Liz Phillips matched me every step of the way.

Liz Phillips…

They were the same age though their backgrounds couldn’t have been more different. She was fromNew Yorkand had degrees from MIT. She was married to a successful businessman, had an attractive daughter who was out in the world, and a life of volunteer work. He had passed two desultory years at Holy Cross playing decent, if undistinguished football. Then he had drawn a high number in the draft lottery and his reason for staying in college had evaporated. A year later he was where he always knew he wanted to be: walking a beat in aBostonpolice uniform. He, too, was married, but to a nurse with whom he seldom spoke and had a son he did not discuss with even his closest friends.

But when he and Liz Phillips were together, there was an undeniable something. Two intellects coming from different worlds, but focused on a common end. They had found the vital clue to Fred Terhune’s death within minutes of one another, though neither knew what avenue the other was pursuing. And God, she was good looking.

Liz Phillips…

His cell phone rang.

“John, it’s Liz…”

He nearly dropped the phone. He held it out in front of him and stared at it. Had thinking about her conjured this call? Seconds later, he realized she was still speaking.

“…painting and, while it’s probably impossible to do anything…”

“Wait, Liz,” he said. “Let me get a piece of paper. You better start over. And it’s wonderful to hear your voice again.” Too forward. Way too forward.

“Roland Evans-Jones and I were just at MFA inBoston. He’s lending a painting to an upcoming exhibition. When the curator took the painting out of the frame, some papers fell out. If the papers are accurate, they describe where someone in Hardington was murdered.”

“When?” Flynn asked.

“This afternoon. We just got back.”

“I mean, when was the murder?”

There was a pause on the end of the line. “June 19, 1889.”

Flynn closed his eyes and started to silently laugh. After a few seconds, he felt he could continue without the risk of hurting her feelings. “I suspect we’re a little late to be able to make an arrest this time around.”

On the other end of the line, Liz laughed. “No, I don’t think you’ll need the sirens on this one. But we think we know where the bodies – there are two of them – are buried. Anyway, Roland wants to invite you to dinner at his house tonight to show you the documents. We’ll show you what we’ve learned and you’ll be able to tell us if you think you can track down the identities of the two men.”

“Liz, I wouldn’t miss it for the world.”

* * * * *

The dinner dishes were cleared. A second bottle of a Gevrey-Chambertin was opened and poured. Roland Evans-Jones, dressed in professorial finery of a bow tie and sweater vest, drew Xerox copies of four pages from aManilafolder and laid them side by side on the dining room table together with a photograph of the painting. Liz and Flynn sat on one side of the table, Roland stood on the other.

“The art world thrives on scandal,” Roland said. “Scandal sells art, scandal fills museums. It doesn’t make any difference is the scandal happened last week or five hundred years ago. Dan Brown writes something provocative about Leonardo DaVinci and all of the sudden, the Louvre has lines down theChamps Elyseesto stare at paintings that everyone except the curators had stopped caring about.”

“Let’s start with the dramatis personae,” he said. “Alan Churchill Lawrence, born 1860 inBoston. On the poor side of the Cabot family, not that anyone among the Cabots could ever be considered poor. Lawrence studied inParis and returned to theU.S. in 1884. By 1889 he was just starting to mature as a painter though he likely wasn’t making much money yet. His family had a compound inFalmouth and he painted there much of the year, turning out scenes of his sisters and cousins at leisure.”

Roland pointed at the first name he had underlined. “John Leslie Breck. He was the driving force behind the Hardington art colony. Born at sea and grew up inBoston. He and Lawrence were the same age. Studied inMunichandParis, including painting with Monet in Giverny in 1887. He wanted to find a Giverny-like place – something with a river, meadows and open fields, and Hardington fit the bill. He and Lawrence had been fellow students at the Academy Julien, and Breck invitedLawrencehere for the ‘inaugural summer’.”

Roland pointed at the next name. “Dennis Miller Bunker. A year younger that Lawrence or Breck. Born inNew York. Studied with William Merritt Chase inNew York, then inParis, where he came to know John Singer Sargent…”

“Why do all these guys have three names?” Flynn asked. “I mean, can’t you just be John Sargent? Were there so many artists around that they all needed to clarify things? ‘Oh, you mean John Singer Sargent, not John Flynn Sargent.’”

Roland’s face fell. “I am among the rabble. Family, Detective Flynn. Family. None of these people were poor. They all drew stipends from somewhere. John Singer Sargent’s parents were peripatetic Americans who moved aroundEurope, searching for the best climate. He and Bunker were from the same social strata, and they were both part of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s circle of ‘bright young men’ she kept around her. Sargent invited Bunker to spend the summer with his family at Calcot Mill in the summer of 1888 – even painted him. You don’t invite strangers to move in for the summer. But you do invite a Bunker if your cousin Gertrude married a Bunker. People waved their family trees like flags; they were their passports and their letters of introduction.”

“Anyway, Dennis Miller Bunker came back toAmerica at the end of 1888 full of ideas about Impressionism and found a group of like-minded people in Hardington. Sadly, he died of heart failure just a year later.”

“The rest of the names are minor artists – Boston-area artists who gave up painting when they failed to sell anything after a few years.”

“Who’s this ‘Chas. Loeffler’?” Flynn pointed to the name on the page, which Roland had not underlined.

“He’s the odd duck,” Roland said. “A friend of Bunker who came to Hardington for the summer to compose music, rather than to paint. He got to be very big in the Boston Symphony hierarchy.”

Flynn nodded, satisfied.

“But here’s the big boy.” Roland thumped the name underlined on the page. “Edward Merrill Cosgrove. Born 1853 in New York. One of the Merrills who would give us, among other things, Merrill Lynch Pierce Fenner and Smith. Joined with the Cosgroves, of the moneygrubbing industrialist Cosgroves, robber barons extraordinaire.”

“Cosgrove knew how to paint, no questions. He also had connections. He studied inParisand hobnobbed with the Impressionists when Impressionism was new. He came back toAmericaand began turning out paintings and portraits that were stunning. His family had about five hundred acres on the ocean atKennebunkportand he started inviting his artist friends to spend their summers on the property whether he was there or not.”

“But Cosgrove also had a dark side, there’s no question. He was ruthless about making certain he was the top dog. Any client who professed to love another painter as much as they loved his work found they were cut off, and the painter found his canvases missing. In 1898, he and a group of American painters seceded from the Society of American Artists and began exhibiting together, much as the Impressionists had done twenty years earlier. Cosgrove didn’t really get along with these other artists, but he had to be there, if you understand.”

“I don’t want to join this club, but if I’m not a member, people will wonder why not,” Flynn said.

“Exactly. And he was invited because of his wealth and connections, not because Hassam or Dewing or Tarbell or any of the others especially liked the guy.”

“Which brings us to Edward Merrill Cosgrove and the ladies,” Roland said. “Cosgrove lived into the 1940s, and his heirs have kept a tight rein on his reputation. Access to his papers is strictly by invitation to biographers who promise to toe the official line. There are a dozen biographies of him, all fawning. But the private stories are altogether different. Despite having a wife and three children, he was a man to whom the words ‘model’ and ‘mistress’ were synonymous. And, if they gave him the slightest encouragement, Cosgrove was not above dallying with the society ladies who paid him to paint their portraits.”

“Do the Cosgrove heirs know about this painting and these papers?” Flynn asked.

“The curator at MFA scanned them and sent them off to a few of her contacts inNew York, basically asking if anyone knew anything about Cosgrove having visited Hardington in 1889,” Roland said. “It is a reasonable assumption that those PDFs made their way to the Cosgrove Trust within an hour after they were sent off. By now, they’ve pulled up the drawbridge and circled the wagons. Any confirmation is going to have to come from some third party. And who that is going to be, I have no idea.”

“What’s the ‘Cosgrove Trust’?” Flynn asked.

“It’s a New York-based group, mostly heirs of Cosgrove and some lawyers,” Roland said. “They control his papers and hold the reproduction rights to most of his paintings. They also have a fairly large number of paintings that are still in the family. Remember: the Cosgroves were wealthy in Edward Merrill Cosgrove’s time. They’ve only grown wealthier in the last century.”

“Got it,” Flynn said.

“There’s one more name,” Roland said. “Howard Langston Edwards, art dealer. A very big name in art inBostonfrom 1870 until the depression. Edwards wasLawrence’s dealer at the time, and believed strongly in him. AndLawrencetrusted Edwards enough to send him these pages from his notebook along with the painting. The question, of course, is how the notebook pages ended up behind the painting rather than in the hands of the police? Maybe Edwards never saw it. It’s also very possible that Edwards read it and was scared to death because he also handled Cosgrove’s work. Remember: Edwards sold aLawrencepainting for $125. A Cosgrove canvas would have commanded $500 and up.”

“So how do you think the pages got to be in the frame?” Flynn asked.

“That, we’ll never know,” Roland said. “What we do know now is that the ‘chain of custody’, so to speak, is unbroken.” He took out a yellowed slip of paper from the manila folder. “In addition to reading every art book I could get my hands on, I’ve been going through boxes of papers in the attic. I bought the painting as part of the estate of William and Louise Green, who both died in 1964 at the ages of 96 and 92, respectively. The Greens were married on July 4, 1889 – he was 21, she was 17, not at all unusual at that time.”

He unfolded the receipt.

RECEIVED from THADDEUS GREEN the sum of ONE HUNDRED AND FIVE DOLLARS for a painting of a house in Hardington, Massachusetts by A.C. LAWRENCE to be delivered to WILLIAM GREEN AND FIANCE. Dated JUNE 23, 1889 by H.L. EDWARDS.

“A wedding present from the groom’s grandparents to the happy couple,” Roland said. “The painting was in Edwards’ hands for no more than a day or two. And now for the piece de resistance.” He took a small photograph from the folder. It showed a stiffly posed young man and woman holding a painting, an elderly couple flanking them. The painting was unmistakably The Wayside Cottage in the same frame.

“All this – including the originalLawrencenote papers – goes into my safe deposit box first thing in the morning,” Roland said.

“So let’s talk aboutBrightonand Carville,” Flynn said.

“Your guess is as good as mine,” Roland said. “They weren’t gentlemen though they dressed reasonably well, and they had tracked down Cosgrove shortly after his arrival in Hardington. But whether we speculate that they were private detectives sent by someone Cosgrove had cheated or the father of one of one of Cosgrove’s models great with child, my guess is that there’s a complaint somewhere on file, either here in Hardington or inBoston.”

“And you’d like me to look,” Flynn smiled. “And then there’s the matter of these graves…”

“One grave, two bodies.”

“Liz said you think you know the location.”

“The cottage is still standing. It’s over onCharles Street.”

“And you think you could find the graves based on the painting?”

Roland pointed to the red flowers in the photo of the painting. “The peony plant marks the spot.”

“Two questions,” Flynn said. “First, what happened toLawrence?”

“That’s a very good question,” Roland said, returning the papers to the file folder. “As near as what I’ve been able to find out in a few hours of research, he left Hardington without finishing any of the paintings he talked about in his notes, although the Bunker and Breck paintings did get completed pretty much as described, so the group at the boarding house stayed on. Lawrencewent back toFalmouthand seldom left the family compound. His reputation went into something of a tailspin and he nearly stopped painting. But in 1895, he abruptly switched gears artistically, moved toNew York, and began painting immigrant life. People fresh off the boat atEllis Island.”

“The Ashcan School,” Liz said.

“Five points to the bright pupil in the front row,” Roland said and smiled. “Yes, Alan Churchill Lawrence, scion of the Cabots, became one of the founders of the Ashcan School of gritty urban realism.”

“Something a sensitive painter might do if he had seen a fellow artist bury two men and get away with it,” Liz said.

“My second question is a little more personal,” Flynn said. He waited until he was certain he had Roland’s attention. “If all this is true –if we find two skeletons under a non-existent peony bush in someone’s back yard, and someone out there can say, yeah, here’s a first-class train ticket with Cosgrove’s name on it fromBostonto Hardington – what does that do to the value of your painting?”

“I haven’t thought about that,” Roland said. He was looking up at the ceiling.

“Bull, Roland. You’ve thought of little else since you left the museum.” Flynn’s eyes were focused intently on Roland’s.

“I don’t need the money, Detective Flynn. I’ve already got more money than I’ll ever spend.”

“Then you’ll have no problem answering the question.”

“Well…”

“Before this, what was the painting worth?”

“An 1887 Churchill Falmouth painting at Skinner’s went for $62,000 in May,” Roland said. “I figured that putting the painting in the MFA show would probably goose the value by about $20,000.”

“Let’s call it $85,000 without the notoriety,” Flynn said. “So what happens to the value of the painting if it’s the key to taking down Edward Merrill Cosgrove?”

Roland’s face paled.

“This is the painting and these are the papers that say the skunk buried two bodies in back of old lady Jeffries’ boarding house. What does the painting go for at Skinner’s now?”

“One five,” Roland whispered.

“I didn’t hear you.”

“My best guess is that in a spirited auction, the painting would bring one point five million.”

Flynn nodded. “Thank you for your honesty.” He picked up his glass and took a sip of wine. The others did the same.

“Why do I think I’m going to be sorry I did this?” Flynn said, mostly to himself. He looked at Liz, who had been silent through most of the discussion. He held out his glass to make a toast. “I’ll help you, Roland. I’ll do it because you’re Liz’s friend. I’ll do it because I wouldn’t be much of a detective if I didn’t like a good mystery. And I’ll do it because, Roland, you’re going to educate me about wine.”

Flynn drained his glass. The other two did the same.