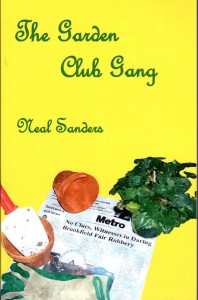

The Garden Club Gang

Genesis of The Garden Club Gang

I’ve long been an afficianado of the peculiar institutions know as New England fairs. They’re a throwback to an earlier era when, at the end of the growing season, families would gather to compete for the biggest pumpkin, the strongest ox or the best sheep. When not showing off their livestock, farmers would look over the newest tractors and threshers. The state fairs elsewhere in the country are corporate behemoths compared to their New England cousins.

I’ve long been an afficianado of the peculiar institutions know as New England fairs. They’re a throwback to an earlier era when, at the end of the growing season, families would gather to compete for the biggest pumpkin, the strongest ox or the best sheep. When not showing off their livestock, farmers would look over the newest tractors and threshers. The state fairs elsewhere in the country are corporate behemoths compared to their New England cousins.

After attending several fairs last summer, I put my author’s cap on and noted several things: first, in an era of debit and credit cards, these fairs are one of the last bastions of a cash economy. Second, many fairs have concurrent flower shows. And, third, there’s a lot of noise and distraction. Naturally, I started thinking, ‘what if…’

The final impetus to writing The Garden Club Gang was the death, at age 89, of a wonderful aunt. When I had all of the raw material together for a story, I asked myself the question, ‘what’s the last thing that dear, sweet Aunt Virginia would have done?’ I was ready to begin writing.

I generally circulate drafts of manuscripts to friends for comment. Several of those drafts went to the ladies of my wife’s garden club who were of the same age as the characters in the story. Their reaction was, in some cases, visceral. “I would never do that,” they said as they threw the manuscript back at me. Some heavy re-writing ensued. The re-reviews from those same individuals was quite positive. The Garden Club Gang was published in 2011.

Reaction to the book was immediate and highly favorable. In November 2013, a second installment of the book was published. Deadly Deeds picks up ‘the Gang’s’ doings four months after the events of The Garden Club Gang.

Below is Chapter 1 of the book. If you’d prefer to download and read off-line, here’s a PDF of the chapter. The Garden Clug Gang is available in both in print and Kindle formats.

Neal Sanders

June 2012

To purchase a copy of The Garden Club Gang, click here.

To see an interview about the book, click here.

The Garden Club Gang in Brief

Committing the perfect crime was just the beginning of their problems.

When Paula, Eleanor, Alice and Jean – ages 51 to 71 – plotted to steal the daily cash gate from the Brookfield Fair, they thought they’d split about $125,000. They pulled off the robbery without a hitch and without witnesses. But, when they counted the money, they found they’d stolen nearly half a million dollars. Puzzlingly, fair officials told police only the smaller amount had been stolen.

In a matter of hours, the Garden Club Gang, as they whimsically called themselves, would find themselves in a battle of wits with the local and state police, a determined insurance investigator and the criminals who were using the fair to launder money. Instead of a lark, the four women find themselves in danger, and dependent upon their own resources to outwit both the law and the crooks determined to find the money and silence those who stole it.

The Garden Club Gang offers four nuanced portraits of interesting women with all-too-credible motives for doing highly unladylike things. If you automatically think any plot that revolves around little old ladies means it has to be a ‘cozy’, then be prepared for a cozy with quite a kick. This is definitely a work of light suspense. The characters are memorable, the action is non-stop and the plot twists until the final page.

The Garden Club Gang

1.

The idea of robbing the Brookfield Fair did not spring full-grown from the minds of the four women. The concept of knocking over the gate receipts – or even an awareness of the phrase ‘knocking over’ – took time to take root. It did so in a series of small events, some of them personal, some of them shared. It is likely that, had those events not occurred within such a small time frame, there might never have been a realization that such a feat was possible.

If there was a moment when the first seed was planted for what would become the Garden Club Gang (as they would call themselves), it was at another, smaller fair, just a month earlier.

Ellen Strong, age 62, stood in front of the flower show entries at the Barnstable Fair on Cape Cod. In her view, none of the four entries in the ‘Delight in the Dunes’ category merited a blue ribbon.

“They’re pitiful,” she said to Alice Beauchamp, who had agreed to accompany her that day in mid-July. Gesturing dismissively at the entry that had garnered the blue ribbon, she said, “There are six, well-established elements of floral design and the person who put this together knows nothing about any of them. What this amounts to is a big pile of flowers in this year’s ‘in’ color. It’s fair to say this person knows squat about any thing other than how to say, ‘charge it to my account’.”

Ellen leaned over and peered at the entry card. Priscilla Lewis, Back Bay Garden Club.

“What Ms. Lewis has,” Ellen said, standing up straight and erect, “is three hundred dollars to throw away on flowers. Pile them high and thick enough, especially the exotic and expensive ones, and they’ll give you the ribbon.”

Alice was silent. She was listening to her friend, but her thoughts were elsewhere. Three hundred dollars for flowers, she thought. Three hundred and seventy-five dollars would get me to Denver to see the birth of my first grandchild. She had looked up the fares on the internet. She had contemplated clicking the mouse to make the purchase. But she didn’t have even remotely that much extra money in her checking account and it would take months to scrape together the fare by scrimping on food or turning off the air conditioner for the summer. And, by then, the fares would have certainly gone up. The only way I am going to get to Denver is to ask my son to send me the airfare, and that would mean asking that wretched harridan of a woman he married.

She shivered at the thought, which in turn caused her foot to start throbbing.

Alice was nine years older than Ellen and her health was reasonably good. She had Medicare now, but the twenty dollar co-pays at the HMO had deterred her from getting her toe taken care of. The toe was one of those annoying things. A hammertoe, they called it. It would only be day surgery and then a week off her feet, but five or six visits to the doctor before and after the operation meant at least a hundred dollars in co-payments.

She ignored the throbbing of her toe.

Ellen noted the silence. She ought not to have mentioned the money. She knew Alice lived on her late husband’s social security and the paltry funds they had accumulated despite all the saving over thirty-six years of marriage. Ellen knew her friend’s financial condition and berated herself mentally for raising such a delicate issue.

But she looked at the terrible flower displays that substituted volumes of expensive blooms for common sense. It wasn’t fair. Rich women who lived in the Back Bay entered competitions seventy miles distant with their Platinum American Express cards as their only credential. Ellen had studied floral design for fifteen years and could create things of beauty from what grew in her own yard.

What we need to do is to win the lottery, she thought. Or rob a liquor store.

What Ellen said was, “Let’s get some lunch. My treat.”

* * * * *

At that same hour in a drab, beige windowless examination room at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Paula Winters absorbed the dismal news she had just been handed.

“It has spread,” her doctor said, simply. “I can’t sugar-coat it.”

The doctor’s words were spoken softly and with empathy. It did not make them less difficult to bear.

Paula’s physician was a highly respected oncologist. Dr. Melissa Peterman’s credentials were impeccable and she was universally considered to be on the cutting edge of breast cancer treatment. Twelve lymph nodes had been biopsied. Cancerous cells had been found in four of them.

“This is Stage III, not Stage IV,” Dr. Peterman said. “There’s no identified metastasis beyond the breast. But we need to discuss aggressive treatment options.”

Paula was still fixed on those first three words. It has spread.

A lumpectomy had been the course of action recommended by a different specialist eighteen months earlier, and had been followed by five courses of radiation treatment. That was back when the cancer was termed Stage I and Paula was assured that the ten-year survival rate was 95%. Until a month ago, the checkups had been clean. Then, an examination had been what her previous doctor called, ‘inconclusive’. That led to the search for and meeting with Melissa Peterman.

Suspect cells in four out of twelve lymph nodes indicated an aggressively spreading cancer and one that could be stopped only with surgery. Moreover, it was possible that even surgery would only slow the cancer’s spread. It was mid-July. Paula thought, I could be dead by Christmas.

And, with that thought came a flood, not of fear, but of regret. What in the hell have I done with my life? she thought. What have I really accomplished in fifty-one years?

In Paula’s view, everything she had ever done had been the ‘safe’ choice. The choices, in turn, had been dictated by her parents, by society and by her husband, Dan. She had gone to the safe state college, gone into the safe profession of nursing, married the man her mother approved of, and left nursing after Dan’s career took off. Her two children were now out of college and on their own. But upon Julie and Perry’s graduation, Dan had dropped his bombshell: he wanted a divorce. A few weeks after the divorce was final, he married a sweet young thing from his company, a woman only a few years older than Julie. A blonde, pretty girl with dazzling white teeth, slim hips and an MBA from the Wharton School.

And Paula was alone.

Melissa Peterman, aware that her patient’s mind was elsewhere, had stopped talking.

Paula looked up at her. “What happens if I decline treatment?”

“The cancer will spread at its own pace, accelerating as it goes.” The doctor’s words were spoken in a way that was clear and unmistakable in its meaning.

“But all we can really do is slow it down,” Paula said. “We can’t cure it.”

Doctor Peterman chose her words carefully but spoke strongly. “I have many patients who were where you are two and three years ago,” she said. “They’re still here, living active, vital lives. And there are new drug therapies coming to market that are very promising.”

And what shape are those two- and three-year survivors going to be in after five years? Paula thought. Are they still in remission or are they living from one round of chemo to the next?

“I need time to think,” Paula said.

“We will need to move quickly,” Dr. Peterman said, emphasizing ‘quickly’.

I’ve never been white-water rafting, Paula thought. I’ve never gone bungee jumping. I’ve never even traveled on my own. Lord, I’ve never taken anything like a risk in my entire life.

* * * * *

At a CVS store in the suburban town of Hardington that same hour, Jean Sullivan waited with growing impatience for her photos. Two teenaged boys manned the check-out counter, trading snickers with one another as they scanned items. A girl of about twenty whose purchases had included a box of tampons had just exited the store and the two boys were elbowing one another, their conversation too muted to be understood but the leering looks on their faces unmistakable.

“Excuse me,” Jean said. “Are my photos ready?”

One of the boys glanced over at the photo desk. “It’ll be a couple of minutes,” he said. His voice betrayed a lack of sincerity in what he said.

“That’s what you said ten minutes ago,” Jean countered.

The one boy shrugged, his dark hair flopping into his eyes. “What can I tell you?”

Do they treat their own grandmother this way? Jean thought. The boys had gone back to an animated conversation about rock groups on tour. Jean wondered if finding the store manager might be the solution to her problem. It had been half an hour. Surely the photos were ready by now.

She glanced down the aisles, looking for anyone in a shirt and tie who might be a manager. But it appeared decision-making authority in the store belonged to these two teenaged boys. A woman, probably in her early thirties with a four- or five-year-old in tow, put her purchases on the counter. The boys efficiently checked out the woman, showing a degree of deference as they did. A woman close enough to their mothers’ age to command attention, Jean thought.

Five more minutes went by. Neither of the boys made any effort to check the photo printer.

I am invisible, Jean thought. I am sixty-six years old, and therefore, I am invisible.

And then an idea occurred to her. If I am invisible, I may as well use it to my advantage.

Jean, a slight woman standing just an inch over five feet, walked to the far end of the counter. The two boys were elbowing each other again, their attention drawn to a buxom young woman, apparently a classmate, who was crouched down looking at cosmetics in an aisle twenty feet away. Jean calmly went through the pile of prints that had accumulated in the photo printer’s output tray. She selected the six prints that were of her grandchildren, emailed to her that morning by her daughter and son-in-law.

She found an envelope and dropped the photos into the sleeve. The envelope went into her purse. She thought for a moment about paying for the photos, but decided that the store should be made to bear some consequences for hiring such oafish, disrespectful children.

As Jean left the store, the two teenaged boys were still watching every movement of the girl in aisle two.

* * * * *

The next day, at the pre-meeting social hour of the Hardington Garden Club, Jean Sullivan showed the photos of her grandchildren to Alice Beauchamp.

“They’re getting so big,” Alice said. “They must be seven or eight.”

“Eight,” Jean said with pride. “The twins’ birthdays were last month.” Jean also knew Alice’s financial predicament and so did not say that she had sent her grandchildren the clothing the twins wore in the photos.

Paula Winters wandered over to see the photos being passed back and forth. Though more than fifteen years younger than Jean and twenty younger than Alice, Paula felt a special kinship to the pair. They were all without spouses and they were gardeners. Some people joined the club just because they had idle time on their hands. Others were content to sit through programs on lavender hand creams and ointments that were poorly disguised sales pitches. Like Paula, Jean took care of elaborate perennial beds at her homes. Alice, she knew, maintained a large plot for vegetables in the town’s community garden.

Jean noted Paula’s pale appearance and wondered if it was health-related. Paula’s bout with breast cancer a year earlier had been well known within the club.

Ellen Strong joined the group, carrying a slice of coffee cake and mug of coffee. Though she had no children of her own, she made appreciative noises upon seeing the photos. She, at least technically, was still married. Her husband, though, had been confined to a nursing home for the past year. Ten years her senior, his Alzheimer’s had progressed to the point that at-home care was no longer possible and he recognized her only intermittently.

The four women spoke of children and grandchildren until the meeting was called to order at ten o’clock. At noon, they found themselves leaving at the same time, walking out into the heat of a New England July day.

“Anyone interested in lunch?” Paula asked. “I’m pulling tomatoes out of the garden by the bushel basket and I’ve got enough chilled gazpacho to feed an army, plus some good bread.”

It had not been a planned invitation. Paula did indeed have an excess of tomatoes and had converted several dozen of the surplus into gazpacho with the intent of giving it away, though at the time she did not know to whom. The idea of lunch simply occurred to her on the spot. Also, while she had no desire to share her most recent diagnosis, she wanted to hear the sounds of voices other than her own in her home.

It was over lunch that Jean first vocalized her belief that she was invisible to all but women of her own age.

“I’ve been thinking about it for the past day,” she said after recounting her experience in the drug store. “After a certain age, we disappear. It’s as though the human mind has been trained to filter us out and ignore us. It wasn’t just those two teenaged boys, either. The same thing happens in grocery stores all the time. I can be at the delicatessen counter at Stop & Shop and wait forever. In a clothing store, no one ever asks if they can help me.”

The other three women nodded their concurrence. Jean was the shortest of the four and her hair was a distinctive silver. Ellen, who remained a blonde, stood a head higher than Jean and weighed perhaps fifty pounds more that her friend, said that she, too, had to raise her voice to get anyone to notice her. Even Paula, younger by more than a decade than anyone else in the room, had to agree that she, too, had passed the point at which she could count on being noticed.

“I was guilty of it,” Alice said, nodding her head. “At the bank, I’d see the men first because they were usually taller. Then the young people because they were noisy. Then the younger women because of their clothes and because they frequently had children with them. The little old ladies came last. They got lost in the background.”

The women spooned their soup, taking in Paula’s large house with its impeccable furnishings. The invitation was an unusual one, for Paula had seldom invited people into her home, and even less so since the divorce.

Paula brought out a tray bearing four glasses and a bottle of white wine. She offered it to the other women.

“Wine doesn’t agree with me,” Jean said.

“Oh, I couldn’t,” Alice said. “I have to drive.”

“I never drink during the day,” Ellen said, holding up her hand to ward off the bottle.

“Well, I’m having one,” Paula said, and poured a glass. “It’s a hot day and a cold glass of wine seems right.” Having a glass of wine on a hot July afternoon was her first act of living dangerously.

The other women watched Paula pour the wine, take an ounce of it in her mouth and roll it around, her eyes closed and a smile of satisfaction on her face. Their resolve quickly melted. The first bottle was emptied and then replaced by a second.

“Have any of you ever been hang-gliding?” Paula asked of the three women when all had had a second glass of wine.

There were looks of bewilderment around the table.

“Went sky-diving?”

They shook their heads.

“Would you if could?” Paula asked.

The others looked baffled, but Jean spoke up. “I could do those things. I went for a ride in a bi-plane when I was a little girl, which I realize today was quite a dangerous thing. Paula, are you talking about things that involve risk, or things that are foolish?”

Paula asked her to explain the difference.

“There are things that offer a thrill, but that involve some degree of risk,” Jean said. “You mentioned sky diving. Parachutes are safe. But if yours is the one parachute in ten thousand that doesn’t open, it means almost certain death. People who ride motorcycles are more likely to be killed in accidents, but people still ride them. They trade the risk for the pleasure it brings. Hang-gliding, though, seems to me to be not so much a sport as a kind of Russian roulette. I read that some percentage of hang gliders are killed every year regardless of their level of experience. It’s like driving on an expressway at a hundred miles an hour. It’s courting death for no reason other than some momentary thrill. It’s foolish, pure and simple.”

“Then leave out the foolish things,” Paula said, pouring more wine. “Would you do something risky – providing it appealed to you – just to be able to know that for once in your life you had not taken the safe choice?”

Once again, as she had at the garden club meeting, Jean wondered if health was somehow at the core of Paula’s odd questions.

Ellen spoke up. “I think about Phil and all the things we didn’t do.” Phil was her nursing-home-confined husband who could no longer make choices for himself. “He wanted to start his own business but we – no, I – decided it was too risky. We never had children because any pregnancy for me would have been a high-risk one. Looking back and knowing what I know now, I’d gladly have taken those chances.”

The others were quiet for a moment. Then Alice spoke. “We never took risks. Especially not financial ones. John insisted on putting our money in savings accounts and savings bonds. He said he didn’t know what the stock market was going to do and he didn’t trust it. Look where it got us.”

The others were stunned by this simple declaration. Alice never spoke of her finances though it was clear to everyone that she was in an increasingly precarious position. She had sold her home following her husband’s death and now, after a disastrous relocation to Florida, lived in Hardington Gardens, a subsidized apartment complex for low-income seniors.

Jean felt it was her turn to speak. “We weren’t brought up to take risks. We were brought up to be mothers and housewives and helpmates. Risks were something men took. Risks were something we were taught to avoid. Al was a wonderful provider, but he was taking the biggest gamble of all – smoking all those years. When he died, I had to learn everything he did, and that meant doing everything with the least degree of risk. Yes, I wish I – and we – had done something for the thrill of it. Because now, I can’t afford to take chances any more.”

“I thought about robbing a liquor store yesterday,” Ellen said. The others laughed. “Now, that’s taking a risk.”

The others wondered why Paula, who had raised the question of risk-taking, did not volunteer her own thoughts on the subject. But it would have been poor etiquette to ask their host such a question. The finished their gazpacho and remarked that it was wonderful. The last glass of wine was drained. And then they departed into the hot afternoon.

* * * * *

Paula thought about what she had heard as she picked up dishes after lunch. They were four women, friends who shared a common interest in gardening. Now, she knew they had a second thing in common: they all regretted what they had not done. It had been a remarkably frank conversation.

Upon returning home from her doctor’s office, Paula had made a list of things she wanted to do. It included going on an African veldt safari, seeing China and Australia, sailing a boat by herself and going white-water rafting down the Colorado River. Unlike the three other women, Paula could afford to do these things. Dan wanted out of the marriage so desperately that he had given up most of their assets plus a share of his business. The money provided a more than adequate income for Paula’s needs.

What she had not been able to do was to manage her cancer.

Paula had been on the verge of telling her friends of the new prognosis. Instead, she listened to the stories of risks not taken and decided not to. For the other three women, the future was constrained by money. They lived on fixed incomes and those incomes did not keep up with their cost of living. Paula felt that Ellen, Alice and Jean were wonderful friends but they could not relate to her longing for adventure and her fear that time for that adventure was running out.

Paula left her kitchen and went to the downstairs half-bath. There, she stood in front of the small mirror over the sink and examined herself. Her chestnut hair was still thick and shiny. The color now came from a bottle but her hair had always been one of her best features. Her face was lean, like the rest of her body. Her nose was small, her pores tight. She was, overall, still an attractive woman. But she saw a pallor in her skin and the dark circles under her eyes that makeup could not hide. The face of a woman with cancer. The face of a woman who has been told how she will die, she thought.

She thought of the years she had devoted to her family. She had been the sole breadwinner while Dan got his business started. “We were brought up to be mothers and housewives and helpmates. Risks were something men took.” Jean had said that, Paula recalled. Dan had taken the career gamble – albeit one softened by the guarantee of her nursing salary. But then, as soon as Julie and Perry were out the door and safely beyond the psychological damage of a parental divorce, he had come home from a business trip and said he was in love with someone else.

Dan had abandoned the security of a corporate job to roll the dice for a bigger payoff with his own business. He had explained what he wanted to do and why, and Paula had gone along with the decision; supporting him both financially and emotionally. Once the risk paid off, though, he had found someone younger and prettier with whom to share the second half of his life. The announcement had been so unexpected – so out of the blue – that Paula had never fully recovered from it. Six months after Dan’s remarriage she had found the lump in her breast.

The end of the marriage and the possible end of her life, all in the same year.

What was it Ellen had said? ‘I thought about robbing a liquor store yesterday.’

Now, that was a risk.